Afghanistan is slipping rapidly towards a state of anarchy. The security situation has degraded to the point where the lavish force protection measures adopted by the Department of State Regional Security Officers and the U.S. Military seven years ago now seem prudent. Media reports attribute the decline to a resurgent Taliban movement in Pakistan, combined with the explosion in illegal drugs and a corrupt, ineffective central government. Many of my colleagues and I believe the crippling of the reconstruction effort by unreasonable risk aversion based security rules has more to do with the current instability than anyone sitting in Washington would care to contemplate let alone admit.

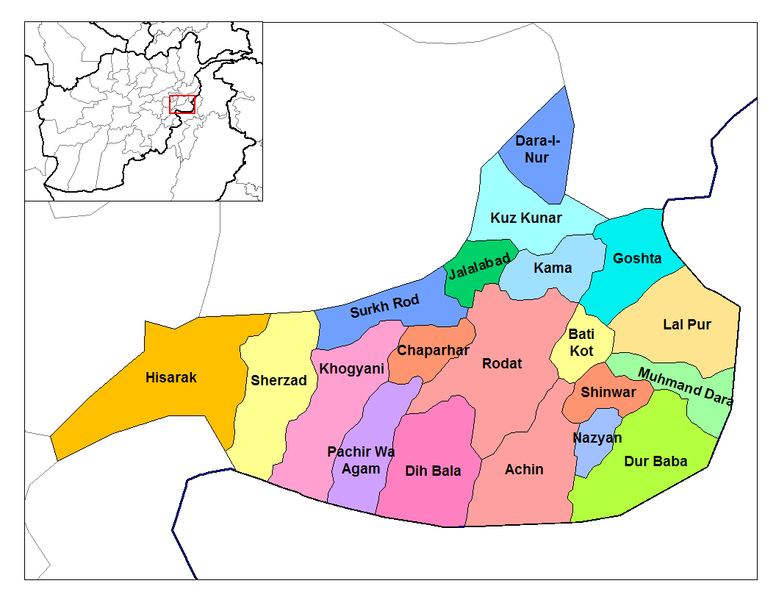

It is easy for those not directly involved in the U.S. effort to highlight and criticize programs that have failed to deliver any quantifiable improvement after years of effort and billions spent. One example: we have spent over 2.5 billion dollars on a police training program, which has produced nothing positive. The Afghan National Police are amongst Afghanistan’s least trusted national institutions, with a well-earned reputation for corruption and criminal behavior. It is difficult to believe how badly we are failing at delivering a stable, functional Afghanistan. It was time to generate some on-the-ground data from a dangerous place, and no district in Nangarhar Province is as hazardous as the Sherzad district.

Nobody would pay me to go to Sherzad and determine the ground truth, but they didn’t need to because Sherzad is home to the village of Gandamak, which guards the Gandamak battlefield. The only way to see the battlefield is with the permission of the men controlling Gandamak, one of whom is my loyal driver, Sherif. In fact, I rent two of my SUVs from Sharif’s brother, who is the mayor of Gandamak.

Having connections is not a magic solution in Afghanistan. I still had a month of intricate negotiations with the Maliks of Sherzad, which started with me hosting them for lunch in Jbad. The term Malik is used in Pashtun tribal areas for tribal leaders. Maliks serve as de facto arbiters in local conflicts, interlocutors in state policy-making, tax collectors, heads of village and town councils. Although they do not officially represent the district government (they are part of a larger board), they speak for the people.

Sherzad district is part of what is known as the “Southern Triangle” in Nangarhar Province. This is one of the areas where we have lost ground over the last year. The Sherzad district administrative center has been attacked three times in the past month by AOG fighters. IED discoveries and attacks are routine, night letters are frequently reported, as are other acts of intimidation. This district is the closest point of the southern triangle to the Taj guesthouse; our staff are from there. Still, they are Pashayi speakers (meaning they are hillbillies originally from Hisarak district) just like the owner.

We spent the two hours at that first meeting as I listened without comment to the standard story about local Taliban being financed by groups in Pakistan. That is not exactly news, and it assumes Westerners don’t understand the difference between Gulbuddin Hekmatyar’s militia (HIG) and the other Peshawar Shura Taliban. Then I was told it was the “bad people from the mountains” who were launching indirect fire and small arms attacks on the US Army’s FOB Lonestar (located next door in Khogyani district), not the local people, despite them being paid by groups in Pakistan. I indicated I had no interest in the Taliban unless the Taliban had developed an interest in me, so Malik deftly switched topics.

The elders said Governor Sherazai promised them jobs and irrigation projects if they stopped growing the poppy, and so they did, but have received nothing. They say that the governor is getting richer by increasing the poppy on his lands in Khandahar while their children go without food or proper clothing. They also said (quite firmly) that if they get enough rain this winter, they are going to start growing the poppy again because they feel tricked out of their share of the booming drug economy. They warned that once they start growing the poppy, they will not allow any foreigners or government people into the district to destroy the crop.

Now for a bit of ground truth from an old Afghan hand. I do not know how much of what they said is true yet. But nobody within the vast US effort could know how much of it is true either. You can’t learn ground truth from one meeting. Everything the Maliks told me, I could have guessed ahead of time. This is the standard litany of complaints (in one form or another) I have heard in meetings from one end of Afghanistan to the other.

I asked the Maliks how they claimed their district was under control when “bad men from the mountains” show up at night to create mischief. They replied, “What do you expect us to say?’ Which was a good point. I then asked if they had the time to take me to the Gandamak battlefield shortly, and they said we could go next week, but it was dangerous, so I should come with a rifle. I asked if I could bring my friends who have rifles, and they said no, that would not be necessary, as they would guarantee my safety. I had no problems with that, as I might be alone, but still be among friends.

I hope that history does not repeat itself.

Keep telling it like it is. I heard the same stuff in Shuras in Kapisa. The lack of economic development and the failure of the local ANP leaves a lot of doors open that could be shut to the Taliban. This is an important story to keep telling. Stay safe!