One of the most incredible aspects of living in Afghanistan is the sense of history that surrounds you as you trek off the beaten path. In the rural districts, the daily routine of the people has remained essentially unchanged for hundreds of years. It is easy to find the sites of historic battles or ancient ruins, which few Westerners have had the opportunity to see. The hospitality of the Afghans is a constant reminder that the capacity for good in people transcends the evil that constantly searches for cold hearts or idle brains where it can embed and grow. An armed society is a polite society, but the Afghans take politeness to an extreme that is at times bewildering.

Yet the Afghans have never been able to govern themselves effectively. Despite their culture of warm hospitality to guests and strangers, their political culture remains polarized, vicious, and deadly. These are tribal lands with a small percentage of the wealthy and a large population of the less fortunate. The “haves” are the leaders with positions determined at birth and not resented by people at the village level because they do not have significantly more than their fellow tribal members. The “have-nots” do not engage in political agitation because they spend most of their lives trying to find their next meal. They are not like the American poor afflicted with health issues from morbid obesity. Poor people here die of starvation, poor children die of exposure during the harsh winters even on the streets of Kabul.

And speaking of politics, what was the first topic discussed when I joined the elders of Sherzad district for a lunch meeting last Thursday? Barack Obama and I’m not making that up. Talk about weird, but let me set the trip up before I get to that.

Traveling into contested tribal lands is a bit tricky. I did not doubt that the Gandamak area Maliks would provide for my safety once I arrived, but I was concerned about the trip in or out. The time-tested decision-making matrix is to examine what the State Department is doing and do the exact opposite. The State Department insists on brand-new armored SUVs with heavily armed contractor escorts in front and behind. I went with an old, beat-up Toyota pickup, without a security escort, and wore local clothing. The Taj manager, Mehrab, served as both driver and interpreter.

The road into Gandamack required us to ford three separate stream beds. The Soviets destroyed the bridges that once spanned these obstacles around 25 years ago. We have been fighting the Stability Operations battle here for seven years, but the bridges are still down, the power plants have not been fixed, and most roads are little better than they were when Alexander the Great came through the Khyber Pass in 327 BC. It took the Soviets around seven years to build the bridges, pave the roads in the southern triangle, and then blow up the bridges and destroy the streets they just built. How did the Soviets completely outclass us in the Stability Operations arena? That’s a question that will never be answered because it will never be asked.

It took over an hour to reach Gandamack, a prosperous hamlet tucked into a small valley. The color of prosperity in Afghanistan is green, as green vegetation signifies water. Villages with access to abundant, clean water are consistently better off than those without. You can see the difference in the health of the children, livestock, and crops.

My host for the day was one of my driver’s older brothers. When I first met Sharif, he told me, “I speak English fluently,” in perfect English. I immediately hired him and issued a quick string of coordinating instructions about what we were doing in the morning, then bid him good day. He failed to show up on time, and when I called him to ask why, it became apparent that the only English words Sharif knew were “I speak English fluently.” You get that from Afghans. But Sharif is learning his letters and has proven an able driver, plus a first-rate scrounger, which is vital for the health and comfort of his ichi ban employer.

The Maliks (tribal leaders) from Gandamak and the surrounding villages arrived shortly after we did. They walked into the meeting room armed; I had left my rifle in the vehicle, which, as the invited foreign guest, I felt obligated to do. Gandamak is in Indian Country, and everybody out here is armed to the teeth. The day started with a shura about what they needed from international NGO’s, followed by a tour of the Gandamak battlefield, and then lunch. I was not going to be able to do much about what they needed, but I could listen politely, which is all they asked of me. I’ve enjoyed visiting battlefields since I was a kid, and when my Dad and I visited the Gettysburg, Antietam, The Wilderness, and Fredericksburg battlefields. I especially enjoy visiting obscure battlefields in remote areas. To the best of my knowledge, I am the only Westerner who has visited the Gandamak battlefield in the last 60 or so years.

As the Maliks arrived, they started talking among themselves in hushed tones, and I kept hearing the name “Barack Obama.” I was apprehensive; I’m surrounded by Obama fanatics every Thursday night at the Taj bar. Talking with them is unpleasant because they know nothing about the man other than he is not Bush and looks cool. They are convinced he is ready to be president because NPR said so. I had no interest in pointing out to the Makiks that Obama has zero experience in executive leadership and will make a terrible president. They have the time and will insist on hashing things out until they understand clearly. I have a wristwatch and a short attention span; this was not a good start.

As I had feared, the morning discussion began with the question, “Tell us about Barack Obama?” What was I to say? His resume is razor thin, but he has demonstrated traits Pashtun Maliks could appreciate, so I described how he came to power in Chicago. Once they understood that lawyers in America are like warlords in Afghanistan and can rub out their competition ahead of an election using the law and judges instead of guns and explosives, they got the picture. A man cold enough to win every office by eliminating his competition before the vote is a man the Pashtuns can understand. I told them that Obama will probably win and that I have no idea how that will impact our effort in Afghanistan.

They asked if Obama was African, and I resisted the obvious answer: Who knows? Instead, I said his father was a Black African and his mother a white American, so he identifies himself as a Black American. They asked if he was joining his mother’s tribe, why wouldn’t he be considered white like her? I didn’t want to explain the racial spoils system in America, so I lied and said the father’s race determined racial classification.

What followed was (I think) a long discussion about Africans; were they or were they not good Muslims? I assume this stems from the Africans they may have seen during the Al Qaeda days. I think the conclusion was that the Africans were like the Arabs and therefore considered the local equivalent of scumbags. They talked among themselves for several more minutes, and I heard John McCain’s name several times, but they did not ask anymore about the pending election, praise be to God. They assured me that they like all Americans regardless of hue, and it would be better to see more of them, especially if they took off the helmets and body armor, because that scares the kids and woman folk. And their big MRAPs scare the cows, who already don’t have enough water and feed, so scaring them causes even less milk to be produced, and on and on. These guys knew how to beat a point to death.

We talked for around 35 more minutes about the anemic American reconstruction effort, their needs, and the rise in armed militancy. The American military visits about once a month and remains popular with the local people. They have built some micro-hydro power projects upstream from Gandamak, which the people, even those who do not benefit from the project, greatly appreciate. The US AID contractor, DAI, has several projects in the district, which the elders believe could be executed more effectively if they were given the funds to manage them themselves. However, despite this, DAI is welcomed and their efforts are greatly appreciated. When I asked who had kidnapped the DAI engineer (a local national) last month and how we could secure his release (which was another reason for my visit), they shrugged and one of them said, “Who knows”? That was to be expected, but I felt compelled to ask anyway.

The elders explained, without me asking, that they are serious about giving up poppy cultivation, but they have yet to see the promised financial aid for doing so. They need a road over which to transport their goods to market. They need their bridges repaired, and their irrigation systems need to be restored to the condition they were in back in the 1970s. They said that these improvements would bring security and increased commerce. One of them made a most interesting comment, to the effect that “the way the roads are now, the only thing we can economically transport over them is the poppy.”

After the talking part of the meeting, the senior Maliks and I piled into my SUV and headed to the Gandamak battlefield.

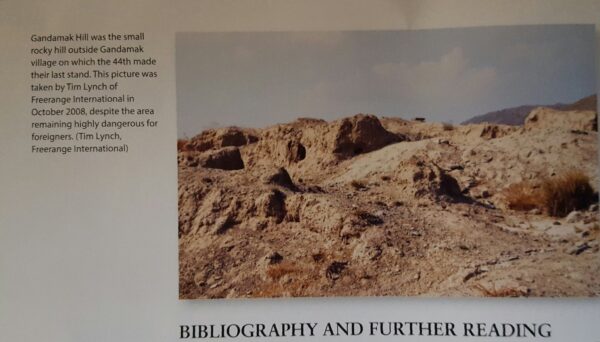

The final stand at Gandamak took place on January 13, 1842. Twenty officers and forty-five British soldiers, most from the 44th Foot, pulled off the road onto a hillock when they found the pass to Jalalabad blocked by Afghan fighters. They must have pulled up on the high ground to take away the mobility advantage of the horse-mounted Afghan fighters. The Afghans closed in and tried to talk the men into surrendering their arms. A sergeant was famously said to reply, “Not bloody likely,” and the fight was on. Six officers cut their way through the attackers and tried to make it to British lines in Jalalabad. Only one, Dr Brydon, made it to safety.

Our first stop was to what the Maliks described as “The British Prison,” which was up on the side of a pass about a mile from the battlefield. We climbed up the steep slope at a vigorous pace set by the senior Malik. About halfway up, we came to what looked to be an old foundation and an entrance to a small cave. They said this was a British prison. I can’t imagine how that could be – there were no British forces here when the 44th Foot was cut down, but they could have established a garrison years later, I suppose. Why the Brits would shove their prisoners down inside a cave located so high up on the side of a mountain is a mystery, and I doubted this story behind what looked to be a mine entrance. It was a nice brisk walk up the very steep hill, and I kept up with the senior Malik, which was probably the point of this detour.

After checking that out, we headed to the battlefield proper. We stopped at the end of a finger, which looked exactly like any other finger jutting down from the mountain range above us. It contained building foundations that had been excavated a few years back. Some villagers started digging through the site looking for anything they could sell in Peshawar shortly after the Taliban fell. The same thing happened at the Minaret of Jam until the central government deployed troops to protect the site. The elders claimed to have unearthed a Buddha statue there, which they figured the British must have pilfered in Kabul. By my estimation, there are 378,431 “ancient, one-of-a-kind Buddha statues” for sale in Afghanistan to the Westerner who is willing to buy one. The penalties for stealing ancient artifacts are severe; tampering with that kind of material is not something reasonable people do in unstable third-world countries.

I do not know where these foundations came from. Back in 1842, the closest British troops were 35 miles away in Jalalabad, and there are no reports of the 44th Foot pulling into an existing structure. We were in the right area – just off the ancient back road which runs to Kabul via the Latabad Pass. My guides were specific that this finger was where the battle occurred, and as their direct ancestors participated in it, I assumed we were on the correct piece of dirt. I would bet that the foundations are from a small British outpost built here, possibly to host the Treaty of Gandamak signing in 1879 or to recover the remains of their dead for proper internment.

The visit concluded with a large lunch, and after we had finished and the food was cleared away, our meeting was officially concluded with a short prayer. I’m not sure what the prayer said, but it was short. I’m an infidel; short is good.

Post Script

The Maliks of Sherzad district never received the attention they wanted from the US Government or the Afghan authorities. Instead, the Taliban came to fill the void and started muscling their way into the district back in 2011. By early 2012, things were bad enough that my old driver, Shariff, called me to see if there was anything I could do about getting the Americans to help them fight off the encroaching Taliban fighters. I was in the Helmand Province by then, dealing with my own Taliban problems, and could offer him nothing. That bothered me then, and it bothers me now, but that’s life.

In August 2012, my old friend Mehrab was gunned down by the Taliban outside his home. By then, several of the men I had shared a pleasant lunch with back in 2008 had also perished fighting the Taliban. Gandamak is now Taliban territory, and the poppy is now the primary source of income. It will be a long time before a Westerner can revisit the old battlefield.

Tim, thanks for telling it like it is. Sure wish I’d stumbled upon your blog years ago. You make me proud to have served in the Corps.

Semper Fi

Scott

I feel ya brother —

“The PBS special contained footage of gigantic crowds of armed Waziristan tribal fighters screaming for death to America which is an intimidating thing to see. But Afghanistan is not Waziristan.yet. A window of opportunity remains for us to get the people solidly behind us which will strip away the ability of Taliban affiliated fighters to move or live in the districts. To take advantage of this window we are going to have to find a new approach, we can no longer shovel in more of the same and expect results. The window is open but we don’t think it will stay open for much longer.”

…………

Thanks for the most interesting story about the battle of the 44th /

The Thunder Run has linked to this post in the blog post From the Front: 11/04/2008 News and Personal dispatches from the front and the home front.

What a day. Great pictures of the Gandamak battlefield. It’s so easy for me to picture what those guys went through. You are right; the world has never seen anything quite like us before. That is one of the reasons that to compare us to the Soviets is to miss the point.

You did a great job of depicting how it is to sit and talk with Afghan elders; how civil and curious they are. They are also quite reticent about certain subjects, like the DAI engineer. It’s odd but not surprising that the Afghans would be so interested in who we elected president. Well, they are going to see if this is a good thing for Afghanistan or not.

Good questions on the bridges and roads and so on. Seven years is a lot of time to make a bit more of a difference. Getting out into the villages once a month or so doesn’t make the impact on either infrastructure, medical needs, or security that would make the Afghan villagers more happy to see Americans.

Great posting! Keep ’em coming, please.

Fantastic post Tim. Your going to give Michael Yon a run for his money if you keep this up. LOL

You know, I love the Roman Road concept that Nagl talked about awhile back. And it sounds like that is what you were hinting at in your post. It is such a simple concept, and it makes total sense. Here is his quote from an interview:

Compared with Iraq, two major differences stand out: geography and opium. How can an effective counterinsurgency best address these problems?

One has to bear in mind that Afghanistan has never in its history had a strong central control of the country. It has never had the infrastructure that is required to reach out from Kabul into the whole country. The challenge in Afghanistan is extraordinary. When the Romans faced an insurgency in a distant province the first thing they did was build a road. And a key part of our counterinsurgency in Afghanistan is building roads so the government is able to reach the people. Then it is important to defeat corruption and create a government that is responsive to the needs of the people. The opium problem finances the insurgency and incites corruption from government agents. The road answer also helps that: We can’t convince farmers to grow wheat rather than opium unless they can ship the wheat to the market. In that terrain if you have to feed a family you can ship a whole lot more opium out on the back of a mule than you can wheat.

http://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/article.aspx?id=2672

The other area that I think is important is telecommunications. Protecting cell towers and protecting the great networking and commerce tool called the mobile phone is vital. I also say make them cheap and plentiful and get those things out there in the hinterland. And with a phone, farmers and merchants can connect with buyers way beyond their standard networks.

With the mobile phone, good roads, power, and bridges, we could see some good progress. Ah, dreaming….. Good stuff. Semper Fi.

Hi Tim,

I have to congratulate you for this blog. I have hardly seen any profound and demonstrative blog like yours.

I served for the German Bundeswehr two times in Mazar, and I fell in love with this beautiful country. Hopefully I have the possibility to return.

Next month I’m going to gain a new experience. I’m going to serve in Iraq, I’m already excited. I work there for a private contractor (Spelato Security Engineering; sse-security.com). It’s a new company, ehich pays good money for traveling around and telling them about the events on the ground. So they can make assessments for private enterprises like oil companies. I think it should be a new and valueable experience.

Sincerly yours,

Peter

Thank you Tim for an actual blow by blow description of life interspersed with history in your sector of this globe. Your link will take the place of ‘Kaboom’ now that CaptG is writing his book.

I would hope that you will do so as well. How I pray your generation would hurry home and bring the real stories to the world before it’s too late. I desire for all of you to take over all of the remaining positions of government and journalism as the last of the despicable 60’s generation dies and turns to dust. Stay Safe

Great, vivid, engaging post. Should be read by many, especially those who have no clue what’s going on in this war but like to pretend they do.

I found your site on Bill Roggio’s LongWarJournal. Thank you so much for being in Afghanistan, for really seeing and listening, and bless your heart for your observations about poverty. I looked at your pictures of that UN refugee camp and almost shoved my fist through my monitor. Today, the UN unveiled a mural (!) for which “they” paid $23 million. And our troops! Thank you for all the good things you write about them. They are the Greatest Generation. More skills, savvy and teamwork than we’ve ever seen. I’m looking forward to your next post.

Tim:

I too came over to your site from a link at the Long War Journal. Interesting reading as I have not kept up much with what is going on in Afghanistan. Was an A-team medic in nam and have spent most of the time since doing health care development work in SE Asia, so I understand what you are saying. Places and people change but the basics of getting to know the situation on the ground and tailoring efforts to meet the needs of the people never change.

I had hopes a few years ago that the emphasis on special ops, what with its own separate command, was heralding a new era of awareness in the military and government. I think to an extent this has happened in Iraq, as many units, including you jar heads are involved in community development activities. However, having regular units listen to sensitivity lectures is not the same as having all your team members thoroughly trained and indoctrinated in working with other cultures from the level of the provincial governor, down to the village elders, and the people themselves, while living in the local community on the local economy as well.

In addition, special ops is not special forces and instead of being at the forefront of activities they have become marginalized to the point where they are not even mentioned by special ops command. As much as I admire the seals putting admirals in charge of special ops command simply demonstrates the focus which is find the bad guys, followed by bang bang shoot ’em up. While very important in its way, it will not win the long war which is strictly dependent on the support of local populations.

Just like vietnam, Al Quada and the Taliban can not defeat our forces militarily; but the war is certainly ours to lose through stupidity, just when victory has become obtainable with the exercise of simple and straight forward measures.