We had to make a run to Kabul last Friday to take some clients to the airport and to pick up new ones. The Jalalabad to Kabul road is considered very dangerous by the military and US State Department, of medium risk by the UN, and minimal risk by me and the hundreds of internationals who travel the route daily. The Taliban or other Armed Opposition Groups (AOG) have never ambushed internationals on this route with the sole exception of taking some pot shots at a UN convoy last week. The reason this route remains open is that it is too important to all the players in Afghanistan to risk its closure; almost 80% of the Afghan GDP flows along it, so the Taliban would have a real PR problem if they cut it, causing a large-scale humanitarian crisis. The criminal gangs and drug lords who cooperate with the Taliban would also become very agitated if the road were closed and probably turn on any real Taliban groups foolish enough to be within their reach if that happened.

We don’t take this run lightly, but we often choose to make it without body armor or long guns because we fear being ambushed by other villainous members of the Afghan security forces. On Friday, our long string of luck ran out, and we became the latest victim of the Afghan security company game. It cost us two sets of body armor, which we cannot replace because you cannot import body armor into Afghanistan, and we were lucky to get away with the weapons. Although we cannot replace the body armor, we were fortunate to get off lightly; it would be difficult for a small company like ours to raise the funds needed to secure the release of an international prisoner from Pul-e-Charkhi prison.

Many think of private security companies as analogous to mercenary bands with all the associated negative connotations. A few of them are shady companies and deserve all the contempt and bad karma in the world to befall their greedy principals. However, most of the companies operating here are well-run and highly professional. To facilitate the implementation of the rule of law in Afghanistan, they formed an association three years ago to support the effort to regulate the industry. That effort has been stymied at every turn by Afghan government officials who seem less interested in regulation or the rule of law than in establishing rules that benefit them.

Just one of many examples; when the Afghan government wrote the first set of regulations, it stipulated that the payment of all fees and penalties would be made to the Ministry of the Interior (MoI). The Private Security Company Association of Afghanistan (PSCAA) has politely pointed out that the new Afghan constitution explicitly states that all fees and taxes must be paid to the Ministry of Finance. There are sufficient international mentors at the Ministry of Finance (MoF) to ensure that fees paid into the ministry are directed directly to the Government treasury.

It was immediately clear that our assistance in Afghan constitutional law interpretation was not well received and the process has gone downhill ever since. There are still no valid laws regarding PSCs in Afghanistan; however, a series of “temporary” licenses have been issued, which every legitimate company in Afghanistan has acquired. These “temporary” licenses are often overlooked by Afghan security services not under the control of the Ministry of Interior (MoI). Afghan security forces have arrested international workers for licensed PSCs who had individual weapons permits from the MoI and thrown them in jail. Although we cannot replace the body armor stolen from us, we were fortunate to get off lightly; it would be difficult for a small company like ours to raise the funds needed to secure the release of an international prisoner from Pul-e-Charkhi prison.

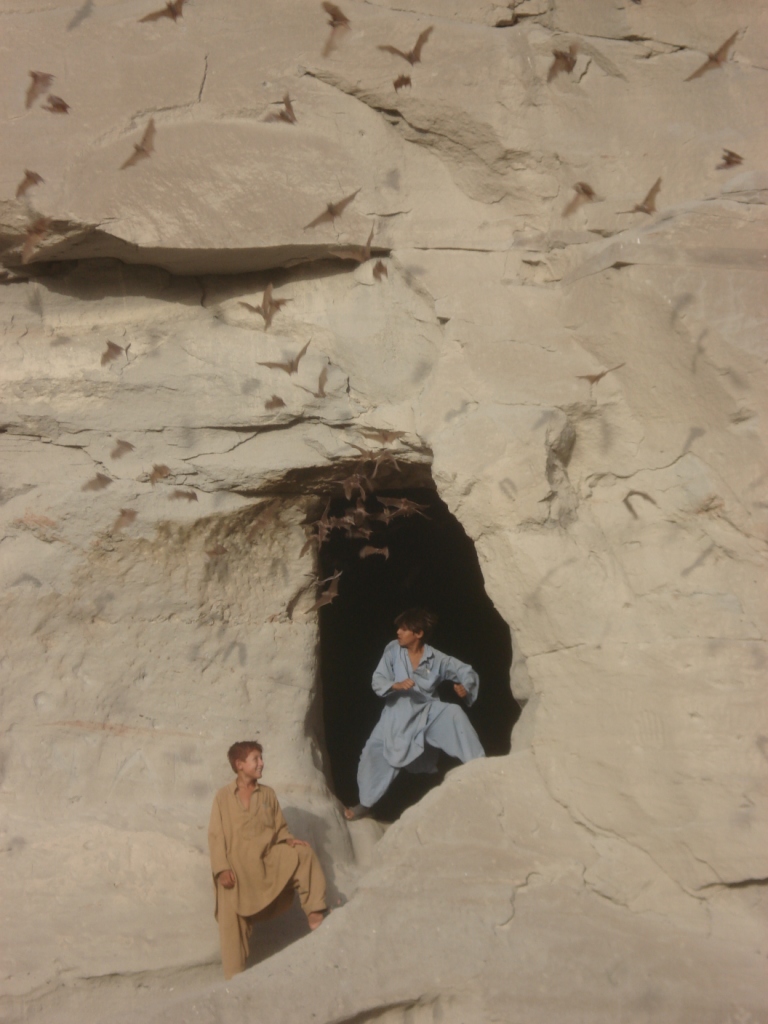

Here is how it went down. We were through the Mahipar pass and almost to Kabul. We approached the last “S” shaped curve before the Puli Charki checkpoint, and an NDS (National Directorate of Security) checkpoint was set up with belt-fed machine guns off to the side, with a good quarter mile separating the east and west checkpoints.

Unfortunately I did not have the Shem Bot with me so I had Haji jann, my good friend and official driver in the contested areas, come down from Kabul to drive us up. This turned out to be a critical mistake because the NDS will not toy with two armed expats when one is driving. If they see an armed Expat with a local driver, it is an indicator for an ” illegally” armed international, which means big cash if they play their cards right. I flashed my weapons permit and license but the boys noted my two clients, PhD candidates from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) – had body armor. In Afghanistan, body armor (used to protect clients), armored vehicles (also used to protect clients), and two-way radios are considered the tools of war, and those of us working here must obtain licenses for them. However, clients change frequently, so we cannot get individual permits for them. We have also never had a problem with this catch-22 because our language skills and charming personalities normally forestall any potential disagreements.

The reason I take Haji jann on all missions into contested areas is because he is a former Taliban commander of some repute (emphasis on former.) He has also been with me through thick and thin, and I truly appreciate him. We talk for hours, although I understand very little of what he says, but we love to chin wag with each other. I heard him say right after we were stopped something like “the armed white guy is a little crazy and I would not arrest him if I were you.” I gave him the ‘what the fuck’ look, and he didn’t smile, indicating that things were serious.

The National Directorate of Security (NDS) wanted the body armor from my MIT clients because they had no license. They also started searching our baggage, which was problematic. I had another gig starting up in Kabul and had extra rounds, magazines, and a first aid kit, all of which are considered illegal (for internationals) in Afghanistan. The “commander,” who is the pot-bellied, slack-jawed fellow in the black fleece, started pulling all my stuff out for confiscation.

I looked at Haji jann who shook his head slightly giving me the go sign and went off like a firecracker at the “commander” who also instantly lost his cool and started to yell back at me. That is a great sign because it indicates fear on his part, and I knew I was not going to lose my spare ammo (which is expensive) and first aid kit. However, they removed the body armor from my MIT charges, and I could do nothing about it. The “commander” gave me a FU smile when his boys stole the body armor because he knew there was no cell signal in the canyon, so what was I going to do? You can only push so far in a situation like this.

This kind of harassment has been routine for the past 18 months in Kabul. We have been spared because we have the proper licenses and travel in pairs, as a rule. Yesterday, I was copied on an email from the security director of the largest US AID contractor in the country regarding one of their projects in the north. It is slightly redacted:

“This afternoon Gen Khalil, commander of the police in Sherbegan, visited one of our well sites demanding to see the PSC license of (deleted) Security. He informed (deleted) that the license expired and that they have until 16:00 to produce a new one or face arrest. Rather than facing arrest all LN guards were stood down and the Expats and TCNs went to Mazar to stay over for the night. This leaves one of our sites uncovered and can have a serious impact on our operations. Can MOI please as a matter of urgency issue new licenses? Maybe someone in MOI can talk some sense into (deleted) head. His no is xxxxxxx”

LN = local national, TCN = third-country national, Expats = armed Westerners

Which brings us to the US Embassy and how they react to news like this, which is (to my mind) deplorable. The embassy response was:

“We do not encourage US citizens to come to Afghanistan for any reason and will not help you in your dealings with the Afghan government. If you are arrested, we will endeavor to ensure you have adequate food and a blanket.”

Since working as a contractor for the Department of State, I have grown to hate it. I was the project manager for the American Embassy guard force and knew precisely what was going on inside our embassy. I’ll write a book about it one day; the tentative title is ‘Diplomacy is Hard When You’re Fat, Stupid, and Arrogant. ‘

A significant problem with the stability operations part of our campaign in Afghanistan is that the local people do not perceive us as serious. The people are our mission; everything we do should be focused on bringing security and infrastructure to the district level to benefit them. After seven years on the ground, we have yet to accomplish basic infrastructure programs. The most efficient way to do this is with a small number of armed contractors who can work at the district level for extended periods. A few people are doing that right now; they are armed because they have to be, and they are doing the daily quality control of Afghan contractors.

We need more support in this area regarding mentoring and quality control of projects awarded to Afghan small businesses. That level of oversight and reporting brings in donor dollars because the money can be accounted for. Donor dollars and expat project management would significantly help break the funding logjam, which currently hampers the district-level reconstruction of roads, irrigation systems, and micro-hydro power generation.

At some point, one hopes the powers will realize this and aggressively support the Americans and other internationals operating far outside the comfortable confines of Kabul. For now, we are essentially on our own, which will ultimately lead to tragedy. Nothing good will come from continued confrontations between dodgy police running “surprise” checkpoints and armed Westerners.