I never attend public observances of military holidays because they make me uncomfortable. My reluctance starts with the knowledge that many of the men who participate at these ceremonies are frauds. It ends with the knowledge that to date, we have failed to protect our fellow citizens from a dire threat emanating from abroad.

In 1998 a former army artillery officer named B.G. Burkett wrote the book Stolen Valor after volunteering to help establish the Texas Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Two things struck him at the organizational meeting for this monument; the first being the number of successful men he knew from his business circle who turned out to be Vietnam Vets. He never knew they served and they didn’t know he had because none of them talked about participating in what was then an unpopular war.

The second anomaly was the number of derelicts who showed up in tattered jungle utilities claiming to be former LRRP’s or SF or SEAL’s or Force Recon. In his book Burkett talks about long range reconnaissance teams (LRRP’s) coming into his fire-base to sleep, refit, re-hydrate and then slip back out into the night. The traits he saw in those men were absent from the derelicts presenting themselves to the Texas commission. So Mr. Burkett submitted freedom of information act (FOIA) requests for the service records on these self proclaimed Rambo’s and guess what? None were what they claimed to be and a majority had never even served in the armed forces.

Back in 2005 CBS news did some actual reporting on this phenomenon which is more common then one would suspect:

…but the phony tales spun by modern impostors — especially those who claim Vietnam service — are no laughing matter. These are the frauds who, every Veterans’ Day, show up at parades and at the Vietnam memorial in Washington in their rag-tag fatigues and flea market medals, telling credulous reporters that Agent Orange or Post Traumatic Stress ruined their lives, and that memories of slitting children’s throats keeps them awake nights. All too often, these suffering “veterans” never set foot in Vietnam — and yet, the images they offer have permanently shaped the way Americans view soldiers from this war: As slovenly, drug-addled baby-killers who loiter on America’s streets when they’re not committing violent crimes. Phony Vietnam vets typically tell tales of Vietnam horrors to explain and excuse their failed lives, Burkett says, and naive journalists uncritically lap them up. Much research proves that — far from being homeless, alcohol-drenched failures — most Vietnam vets are healthy, mentally stable, successful men who deserve their country’s respect.

The fact that military service has once again become respectable means America is currently fielding a bumper crop of frauds claiming to have fought somewhere or other — and they have the medals to prove it. Last May, FBI Special Agent Thomas Cottone, Jr. told the Wall Street Journal that for every actual Navy SEAL today, there are at least 300 imposters. And more than twice as many people say they’ve received the Medal of Honor than the 124 living recipients who actually earned it.

In 2006 the Stolen Valor Act, based in part by the book, was signed into law making it a crime to lie about being a military hero. In 2012 that law was struck down by the 9th Circuit Court as being a violation of the 1st Amendment. The Supreme Court followed up with a ruling that said fraudulently wearing medals of valor was also covered by the 1st Amendment. The rampant fraud thus continues to this day under the protection of a constitution the frauds did nothing to defend.

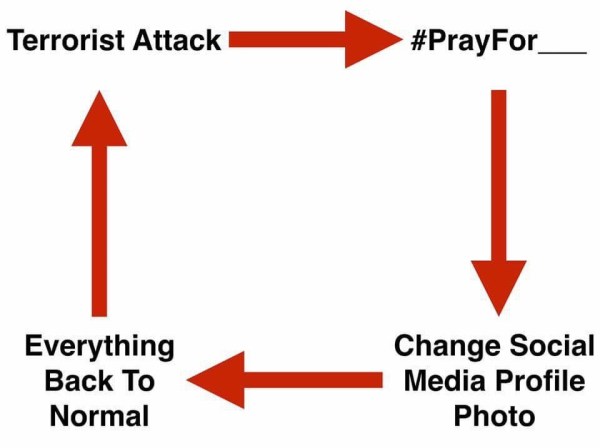

I also have a problem with the remark “thank you for your service”. The reason that kind gesture of support is unsettling is it’s premise. Often I hear on TV or read in the print that the military is “over there” to keep the enemy from being “over here”. But the enemy is here.

Homegrown Jihadi’s John Allen Muhammad and John Lee Malvo, in October 2002, paralyzed the greater Washington DC area for 3 weeks with a carbine and a white van. Our military could not have stopped the Islamic extremist who were already here but it could have reduced the number coming in from abroad if only we had killed OBL in 2001 and come home.

The military has not battled a foe who represents an existential threat to America or our way of life since WWII. All the fighting we have done for the last 16 years in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, and Libya has not made the population of America safer; it has made us less safe. We are less safe because Jihadi’s use our fighting strength in Muslim lands as a way to recruit. In their recruitment propaganda they are David and we are Goliath; they are the underdog and we the gigantic bully who seeks to dominate and them eradicate Islam. The ranks of suicidal, militant Jihadists have grown as a result of our efforts to fight it overseas.

Common sense measures to mitigate the threat of Islamic terrorism are dead on arrival today. The Democratic party and their adjuncts in the legacy media and academia hysterically smeared a proposed 90 day pause on immigration from seven countries designed to tighten screening of immigrants from those countries as a ‘Muslim ban’.

The largest Muslim country in the world is Indonesia; only one of the seven countries identified for that pause (Iran at number 7) were in the top ten Muslim majority countries in the world. That pause was well within the authority of an Executive Order but the liberal judiciary insisted on interpreting what they thought was inside the presidents head, not the law.

Trump’s order “speaks with vague words of national security, but in context drips with religious intolerance, animus and discrimination,” Chief Judge Roger L. Gregory wrote. He said the order conflicts with the First Amendment’s ban on “laws respecting an establishment of religion.”

Not every citizen from those seven countries is a Muslim. Islam is not a monolithic religion anyway. Shia’s do not practice Islam like Sunni’s; Wahhabi Islam is not the same as the interpretations of Salafism. Cultures absorb religion, religion does not absorb cultures which is why, in Afghanistan today, the people still celebrate Zoroaster holidays like Naw-Ruz. How similar are the practice of Catholicism to Baptists in America today? They’re not remotely the same but for some reason, to our elites, all forms of Islam are the same. Any attempt to differentiate among them is ‘Islamaphobia’ a word best defined (by Andrew Cummings) as “a word created by fascists, and used by cowards, to manipulate morons.”

The enemy we face comes directly from the exportation of the Wahhabi variation of Islam. President Trump is the first world leader to throw down the gauntlet in his speech last week where he told the Gulf Arabs, the exporters of Wahhabi Islam:

The nations of the Middle East will have to decide what kind of future they want for themselves, for their countries, and for their children. It is a choice between two futures – and it is a choice America cannot make for you. A better future is only possible if your nations drive out the terrorists and extremists. Drive. Them. Out. DRIVE THEM OUT of your places of worship. DRIVE THEM OUT of your communities. DRIVE THEM OUT of your holy land, and DRIVE THEM OUT OF THIS EARTH.”

The ninety day pause in immigration that President Trump proposed targeted countries known to export the Wahhabi strain of Islam. It was a reasonable move by a man who takes the protection of American citizens seriously. You could argue there should have been more countries, not less, on that list but you can’t argue that the intent was clear and just.

We have more to worry about that Islamic Terrorism. President Trump is finally addressing the threat of North Korea before they develop a multi stage rocket system to deliver their nukes. Preventing the NORKs from developing a delivery system that gives them the ability to strike us is critical if we are to prevent the specter of nuclear war. Yet the press focuses not on that but on an allegation that the President told another world leader we had two nuke subs in the area. What does that even mean? Was he saying we have two subs within striking range of North Korea? Every sub we have can strike North Korea from any ocean in the world. They don’t need to be close – so why all the hysteria?

Our youth are not being educated in the basics of reading, writing and arithmetic which, when combined with instruction on logic, reason and the history of western civilization enables citizens to participate in rational civic discourse. They are being indoctrinated into a world view that negates the positive contributions of western civilization and replaces it with the soft virtue of victimology. Our children are being taught that ‘truth’ is a cultural construct rendering them unable to understand the basic truth that not all cultures are equal, not all cultural diversity good.

Despite of the enormous influence of toxic progressive-ism in America we are still fielding the finest armed forces the world has ever known. None of the problems I am writing about are the fault of the American soldier, sailor, airman or Marine. Those of us who have served should be thanking you for our service. Not many Americans can qualify to join the armed forces today. Of those that do and choose to serve the vast majority find their time under arms to be a privilege. We serve with men and women who (for the most part) are smart, fit, motivated and serious. There are no comparable experiences available to civilians. Service is a privilege few understand and fewer still appreciate but those who serve know they were the lucky ones.

The military men and women who paid the ultimate sacrifice in War deserve the respect that comes with a national holiday set aside to honor them. They do not deserve to have their legacies tarnished by frauds. They do not deserve to have their sacrifices made moot by political and military leaders who deal, not with reality, but the expedient of the progressive liberal Narrative.

There are several men who will be remembered in my prayers tonight and not all of them are Americans. But they were all warriors; they lived the virtues of discipline, courage and self-sacrifice. They never failed to move towards the sound of guns. They were better men than me and I was blessed to have known them. I will honor them in my own way today skipping ceremonies officiated by self serving politicians and constitutionally protected frauds.