Last week I received a polite email from Professor Richard Macrory of the Centre for Law and the Environment, University College London, asking me for permission to use some of my photos of the Gandamak battlefield in his upcoming book on the First Afghan War. I said it would be an honor, and I believe the book will come out next year. In the meantime, I’m re-posting my Gandamak story because it differs from every other Gandamak story from Afghan-based expats. This Gandamak tale is about the battlefield, not one of the best bar/guesthouses in Kabul

Traveling into contested tribal lands is a bit tricky. I had no doubt that the Malicks from Gandamak would provide for my safety at our destination but I had to get there first. Given the amount of Taliban activity between Jalalabad and Gandamak the only safe way to get there and back was low profile.

The road into Gandamack required us to ford three separate stream beds. The Soviets destroyed the bridges that spanned these obstacles around 25 years ago. We have been fighting the Stability Operations battle here for seven years, but the bridges are still down, the power plants have not been fixed, and most roads are little better than when Alexander the Great came through the Khyber Pass in 327 BC. The job of repairing and building the infrastructure of Afghanistan is much bigger than anyone back home can imagine. Given their current operational tempo and style, it is also clearly beyond the capabilities of USAID or the US Military PRTs to fix it. These bridges are still down (as of 2015) and may never be fixed in our lifetimes.

It took over an hour to reach Gandamack, a prosperous hamlet tucked into a small valley. The color of prosperity in Afghanistan is green because vegetation means water, and villages with abundant clean water are always significantly better off than those without.

My host for the day was the older brother of my driver, Sharif. When I first met Sharif, he said, “I speak English fluently,” and smiled. I immediately hired him and issued a quick string of coordinating instructions about what we were doing in the morning, then bid him good day. He failed to show up on time, and when I called him to ask why, it became apparent that Sharif only knew the words “I speak English fluently.” You get that from Afghans. But Shariff is learning his letters and has proven an able driver, plus a first-rate scrounger.

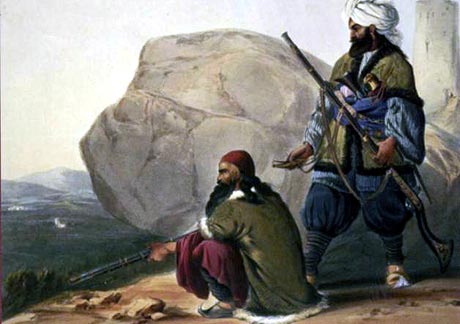

The Maliks (tribal leaders) from Gandamak and the surrounding villages arrived shortly after we did. They walked into the meeting room armed; I had left my rifle in the vehicle, which, as the invited foreign guest, I felt obligated to do. Gandamak is Indian Country, and everybody out here is armed to the teeth. I was a guest; the odds of my being harmed by the Maliks who asked me were zero. That’s how Pashtunwali works. The order of business was a meeting where the topic was what they needed and why they couldn’t get help. Then we were to tour the hill outside Gandamak where the 44th Foot fought to the last man during the British retreat from Kabul in 1842, followed by lunch. I could not do much about the projects they needed, but I could listen politely, which is all they asked of me. Years later, I could lend them a hand when they needed it, but I was a security guard, not an aid guy at the time of this meeting.

As the Maliks arrived, they started talking among themselves in hushed tones, and I kept hearing the name “Barack Obama.” I was apprehensive; I’m surrounded by Obama fanatics every Thursday night at the Taj bar. Talking with them is unpleasant because they know nothing about the man other than that he is not Bush and looks cool. They are convinced he is ready to be president because NPR told them so. Pointing out to the NGO girls that Obama can’t possibly be prepared to be the chief executive because he has zero experience in executive leadership is pointless, and I did not want to have to explain this to the Maliks. They have time and will insist on hashing things out for as long as possible to reach a clear understanding. I have a wrist watch and a short attention span; this was not starting well.

As I feared, the morning discussion started with “Tell us about Barack Obama?” What was I to say? His thin resume is a problem, but he has risen to the top of the democratic machine, and that took some traits Pashtun Maliks could identify with. I described how he came to power in the Chicago machine. Not by trying to explain Chicago, but in general terms, using the oldest communication device known to man, a good story. A story based on fact, colored with a little supposition, and augmented by my colorful imagination. Once they understood that lawyers in America are like warlords in Afghanistan and can rub out their competition ahead of an election using the law and judges instead of guns, they got the picture. A man cold enough to win every office he ran by eliminating his competition before the vote is a man the Pashtuns can understand. I told them that Obama will probably win and that I have no idea how that will impact our effort in Afghanistan. They asked if Obama was African, and I resisted the obvious answer: Who knows? Instead, I said his father was African and his mother a white American, and so he identifies himself as an African American. I had confused my hosts, and they just looked at me for a long time, saying nothing.

What followed was (I think) a long discussion about Africans; were they or were they not good Muslims? I assume this stems from the Africans they may have seen during the Al Qaeda days. I think the conclusion was that the Africans were like the Arabs and therefore considered suspect. They talked among themselves for several more minutes, and I heard John McCain’s name several times, but they no longer asked about the pending election, praise be to God. They assured me that they like all Americans regardless of hue, and it would be better to see more of them, especially if they took off the helmets and body armor, because that scares the kids and woman folk. And their big MRAPS scare the cows who already don’t have enough water and feed, so scaring them causes even less milk to be produced, and on and on and on; these guys know how to beat a point to death.

We talked for around 35 more minutes about the anemic American reconstruction effort, their needs, and the rise in armed militancy. The American military visits the district of Sherzad about once a month and remains popular with the locals. They have built some micro-hydro power projects upstream from Gandamak, which the people (even those who do not benefit from the project) greatly appreciate. The US AID contractor DAI has several projects in the district, which the elders feel could be done better if they were given the money to do it themselves, but despite this, DAI is welcomed and their efforts are much appreciated. When I asked who had kidnapped the DAI engineer (a local national) last month and how we could go about securing his release (which was another reason for my visit) they shrugged and one of them said “who knows”? That was to be expected, but I felt compelled to ask anyway. They know I have no skin in that game and am therefore irrelevant.

The elders explained, without me asking, that they are serious about giving up poppy cultivation, but they have yet to see the promised financial aid for doing so and thus will have to grow poppy again (if they get enough rain, inshallah). They also need a road to transport their crops to market once their fields are productive. Then they need their bridges repaired and their irrigation systems restored to the condition they were in in the 1970s, and that’s it. They said that with these improvements would come security and more commerce. One of them commented most interestingly: “The way the roads are now, the only thing we can economically transport over them is the poppy.” A little food for thought.

At the conclusion of the meeting’s talking part, the senior Maliks and I piled into my SUV and headed to the Gandamak battlefield.

The final stand at Gandamak occurred on the 13th of January 1842. Twenty officers and forty-five British soldiers, most from the 44th Foot, pulled off the road onto a hillock when they found the pass to Jalalabad blocked by Afghan fighters. They must have pulled up on the high ground to take away the mobility advantage of the horse-mounted Afghan fighters. The Afghans closed in and tried to talk the men into surrendering their arms. A sergeant was famously said to reply, “Not bloody likely,” and the fight was on. Six officers cut their way through the attackers and tried to make it to British lines in Jalalabad. Only one, Dr Brydon, made it to safety.

Our first stop was at what the Maliks described as “The British Prison,” which was up on the side of the Jalalabad pass about a mile from the battlefield. We climbed up the steep slope at a vigorous pace set by the senior Malik. About halfway up we came to what looked to be an old foundation and an entrance to a small cave. They said this was a British prison. I can’t imagine how that could be – there were no British forces here when the 44th Foot was cut down, but they could have established a garrison years later, I suppose. Why the Brits would shove their prisoners inside a cave located so high up on the side of a mountain is a mystery to me, and I doubt this was the real story behind what looked to be a mine entrance. It was a nice brisk walk up a very steep hill, and I kept up with the senior Malik, which was probably the point of this detour.

After checking that out, we headed to the battlefield proper. We stopped at the end of a finger, which looked exactly like any other finger jutting down from the mountain range above us. It contained building foundations that had been excavated a few years back. Some villagers started digging through the site looking for anything they could sell in Peshawar shortly after the Taliban fell. The same thing happened at the Minaret of Jamm until the central government sent troops to protect the site. The elders claimed to have unearthed a Buddha statue at the Gandamak battlefield a few years ago, which they figured the British must have pilfered from Kabul. By my estimation, there are 378,431 “ancient one-of-a-kind Buddha statues” for sale in Afghanistan to the westerner dumb enough to buy one. Their excellent fakes, and they better be, because the penalties for trafficking ancient artifacts are severe in Afghanistan.

I do not know where these foundations came from. In 1842, the closest British troops were 35 miles away in Jalalabad, and there are no reports of the 44th Foot pulling into an existing structure. We were in the right area – just off the ancient back road to Kabul via the Latabad Pass. My guides were certain this finger was where the battle occurred, and as their direct ancestors participated in it, I assumed we were on the correct piece of dirt. I would bet that the foundations are from a small British outpost built here, possibly to host the Treaty of Gandamak signing in 1879 or to recover the remains of their dead for proper internment.

The visit concluded with a large lunch, and after we had finished and the food was removed, our meeting was officially ended with a short prayer. I’m not sure what the prayer said, but it was brief. I’m an infidel; short is good

Post Script

The Maliks of Sherzad district never received the attention they wanted from the US Government or the Afghan authorities. Instead, the Taliban came to fill the void and started muscling their way into the district back in 2011. By early 2012, things were bad enough that my old driver, Shariff, called me to see if there was anything I could do about getting the Americans to help them fight off the encroaching Taliban fighters. I was in the Helmand Province by then, dealing with my own Taliban problems, and could offer him nothing. That bothered me then and bothers me now, but that’s life.

In August 2012, my old friend Mehrab was gunned down by the Taliban outside his home. By then,, several of the men I had shared a pleasant lunch with back in 2008 had also perished fighting the Taliban. Gandamak is now Taliban territory, and the poppy is now the main source of income. It will be long before a Westerner can revisit the old battlefield.

Great to see you writing again Tim, hope you’re doing ok.

Doing fine Dave – fighting the strategic battle on our war on terror by working in the South Texas oil biz. Fracking – making us energy self sufficient and doing it despite, not because of, our inefficient government

Glad to hear that you landed on your feet.

May be a little early to declare victory David but I’m getting there.

YEY – Hes Back !!!!! —

lets tell a story ey?!? //

Baba Ken my brother – yes I will post something on ISIS soon

next post, is this so called iSIS threat real, and if so, are the pahtans on board with them?/? I would think not — but lets hear your opine baba T

The long silence is broken. So glad to hear from the master story teller, even from South Texas (most think of the whole state as south). Glad to hear you have a working agent. Most interested in hearing your views of ISIS.

Hey Zail – it’s nice to be back my friend and I appreciate your comment and support

This was amazing trip, you have balls. I’d very much like to go and pay my respects some day, but I too fear it may be a long time, certainly based on my own experiences of the country. Well done you, thank you for the article and the pictures.

Not a problem brother – it will be a long time before a Westerner will able to do that again and I’m really glad I did while the door was still open