Tim san really really wanted me to post our project descriptions for you readers even though I haven’t had enough time to them justice. (I’ve just returned from a very intense install / training / opening week in East Cleveland, Ohio where there was a more tense security presence than much of Afghanistan.)

One ton of machines and materials for the Jalalabad Fab Lab hit the ground in June 2008 and we’ve been busy transforming the pile of equipment into a living breathing community. We’ve accomplished a lot in 6 months, in addition to installing and configuring the machines, we’ve also started several projects with local users. That $40,000 I mentioned in the last post covered all of the below projects, plus a ton of work in infrastructure, groundwork, research and discussions. What I find really great is all the projects described have been also been continued by Afghans after the international visitors left. Truly “teach a man to fish” stuff here.

T-Shirt Club

The t-shirt club makes custom shirts for profit. They use a computer drawing program and the internet for designs and a computer-controlled knife cutter to make the silk screen mask. Then they print the shirt (or anything) by hand. Club members use a computer spreadsheet to track their orders and cash ledger. In the first two weeks of operation, club members have already experienced business considerations such as pricing, cash accountability, stock management, quality control, delivery requirements and consequences, business goals and plans, scaling, and more.

In 14 days the club earned $142 “take home profit”, paid $19 in “use fees” to the FabLab and deposited $20 into the club account. (On day 15 the students received 6 more orders!) More than a week on and the club is still going strong with a small amount of remote mentoring. Club members are approximately 15-18 years old. More information on the T-shirt Club here.

The “use fee” paid to the FabLab is profoundly encouraging. The monthly burn rate at the lab is approximately $1200 – $1500 – and every single cent goes to directly Afghans in one way or another. A single club of 4 youth was able to generate almost 2% of those fees in their first two weeks by contributing only $1 per shirt… The market for custom T-shirts at $10 each is much bigger especially once these kids set up at the FOB and PRT bazaars. And the “use fee” from the FabFi and other projects have the potential to generate much more. It will take a while before the lab is fully self-sustainable but there is a reasonable path.

User Training (future clubs?)

Stamps, challenge coins, music boxes (in particular microcontroller-based circuits), Picocrickets and Scratch graphical game design and programming.

milling custom rubber stamps

milling custom rubber stamps casting custom challenge coins

casting custom challenge coins

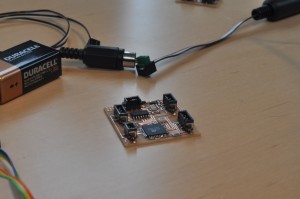

FabFi : DIY Wireless

FabFi antenna hardware are completely made or sourced locally, the total cost is around $65-$75 in materials for each one depending on the size of the reflector. Reflectors “printed” in the lab are coupled with specially configured commercial access points / routers and can be used to make wireless high speed connections as far as 15 km away. Within the FabFi local network we’re achieving speeds of 4.5+ Mbps. And there’s nothing to stop the users from making more and expanding the network.

As of the end of January 2009, three main links were made: one to the school in our local village of Bagrami, one to the public hospital, and one to an NGO near to the hospital. To make the last two links, both in Jalalabad City center, we made a long-haul link to the water tower (the second highest structure in Jalalabad) then two downlinks fan out from the water tower. In addition to the technical achievement, the water/FabFi transmit tower is now a shared resource for all of the various organizations within the hospital. Since much of Jalalabad City can “see” the tower and are eager to also point downlink antennas at the FabFi, there is budding neighborhood pressure on the hospital to keep the resource working and serviced.

The FabLab freely shares its 2+Mbps down / 485kbps up Intelsat internet connection with anyone that connects to the FabFi network. All current sites are expected to fan out with more links; we’ve had Afghans working with us that are very close to being able to make and install future links. This will ultimately turn into a “FabFi Club” where members make money from making, installing, and maintaining the FabFi network. The prices, membership, and level of service have yet to be worked out. The design is open sourced, meaning that anyone can download the design and configuration files for free; club members would get paid for the service of actually buying the raw materials, constructing the antennas, configuring and installing the system, and so forth.

FabFi and GATR SatCom Antennas on Fab Lab Roof

FabFi and GATR SatCom Antennas on Fab Lab RoofMore information on FabFi in Afghanistan here, including a FabFi 1.0 distribution download site.

Digital Pathology

20 years ago the pathology lab in the medical school was well known as one of the better labs in Asia. Today the lab looks exactly as it did 20 years ago… complete with 20 year old supplies and processes.

40X view

40X view

of sample a frozen section sample

a frozen section sample

on a digital microscopeHow does technology (especially communication) change everything? With Dr. Mendoza from San Diego Sister Cities Association, we installed, integrated, and demonstrated a frozen section machine, digital microscope, and internet connection to obtain “real time” remote pathology consultations on a sample from a volunteer. See the full story here.

Local Copy of the Internet

A proxy server was installed between the Internet and the FabFi network. Much web content doesn’t change very quickly and a copy kept in country, synced only once in a while, means ridiculously fast “internet” and significantly eased load on the satellite link. This means that most of the traffic is only within the country. The current FabFi has 4.5Mbps bandwidth; the connection to the Internet is limited by the satellite bandwidth. (By the way, the “real” Internet works the same way, with copies of itself physically all over the world, but usually done by slightly more professional folks with bigger budgets for better server farms and power systems.) Right now the proxy server keeps a copy of anything anyone clicks on; in the near future we’ll mirror Wikipedia and other open educational and informational sources.

MIT Open CourseWare

Check out a long time MIT favorite:

Check out a long time MIT favorite:

Prof Lewin demonstrating that the period

of a pendulum is independent of the mass

hanging from the pendulum in Lecture 10

of MIT 8.10: Physics I.

Every single undergraduate class and many of the graduate classes taught at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology has been painstakingly recorded, indexed, transcribed and compiled along with all the materials from the classes. You can watch any class just as if you were in the classroom. Free. And all of Open CourseWare is online in the FabFi network.

From anywhere in the world you can access MIT Open CourseWare; if you’re lucky enough to be connected to the FabFi network in Nangarhar Province you won’t have a wink of delay even with an entire classroom streaming the video courses.

Bagrami School Teacher Laptop Training

Approximately 9 teachers from the school in Bagrami wanted to learn basic computers. Teachers have been loaned OLPCs through the end of this semester so they can take the computers home to spend hands-on time with them. Ultimately these teachers’ students will have OLPCs or similar laptops and as the teachers learn to use the computers themselves, they are thinking about how they will integrate the availability of technology into their lesson plans. The teachers currently come to the FabLab to charge the laptops, connect to the internet, and use the printer (we hope in the near future they will also begin using the other Fab output devices). One teacher in particular is very good in English and has had about 2 weeks more of training from the FabFolk than the other teachers and is leading getting the other teachers involved. Most teachers involved are approximately 23-27 years old. More on the Bagrami teachers’ computer training here and the proposed FabLab/OLPC Bagrami field trial here.

Bagrami Online

The congruence of the FabFi network and teacher laptop training projects above naturally led to installing a FabFi connection at the school in our village of Bagrami. The headmaster and department of education have agreed to allow anyone to use the school rooms (and internet connection) outside of school hours. A wireless access point was installed at the Bagrami school and a small radius of houses nearby can also connect to the network without being inside the school walls. There is great interest in the small village of Bagrami (aproximately 4,000 to 5,000 inhabitants) to extend the coverage across all of Bagrami. It is the children of Bagrami that are our constant students in the FabLab and so they are ideally poised to fabricate as many antennas as they wish. This is a village that does not have grid electricity or running water. Some residents share the cost of running a single generator, the others simply don’t have electricity. Ever. It’s funny to think that you could be lying in the sun on your mud roof enjoying faster net speeds than, well, me at my apartment in Cambridge, MA.

discovering Wikipedia in Bagrami

discovering Wikipedia in BagramiIn places like Bagrami, access to computers and the internet can be life-changing. Nekibulah’s brother, for instance, is interested in medicine but has absolutely no access to any information on the subject. A simple google search for “health” had him excited in no time at all, and I was glad to watch the attending group devour a page on woman’s health (including sexual health) without even batting an eyelash. In contrast to his brother, Nekibulah was more interested in information about Afghanistan and Islam. The tension between traditional cultural values / religious beliefs and the desire for the opportunities of western (for lack of a better term) society is palpable in these moments of discovery. “Are there Muslims in America?” “When you have a guest in your house would you have tea together?” (From Keith’s blog entry the day Bagrami link went online)

Online Lab Journal

It’s still not perfect or posted in the correct place, but we’ve got the teachers and lab assistant posting the daily lab journal online. (It’s supposed to be here but it’s probably in the stream here.) Management, finances, accountability, and responsibility, it’s all being developed wobbly and imperfectly in the open so you can see exactly what’s going on.

Weather Station (Almost) Online

If you go to weather.com and try to find weather for Jalalabad, you’ll get either Kabul or Peshawar weather, and neither are at all close or similar in weather. We installed a weather station – anemometer, temperature, barometer, etc. and had a blast teaching students about atmospheric sciences. Students from Bagrami are deeply connected to farming – they don’t need a gadget to predict the weather but the quantization of the data was world shifting. We realized too late that we don’t have the “special software” to gather the data and post it to something like weather.com, making Bagrami yet more connected with the world. We ran out of time to play with the system which has a serial interface and see if we can pipe the raw data directly into a FabFi router. For now, FabLab users carefully record the temperature and conditions in a journal and are learning how to track and graph the data.

Have you really made it all the way down to here? I’m still plodding through our photos and videos and I wish I was ready with an album to give you a taste of how exciting and vibrant the region as well as our students are — really quite opposite than what you might see on TV.

Interested in helping? We need everything from back end geek work to front end install / maintenance work, curriculum and teaching, small business mentoring, plus other specialist knowledge in pretty much anything that can be useful in Bagrami and beyond that can be enabled or enhanced with technology. If you’re good at something, I can probably use the help.