As our two-decade involvement in Afghanistan winds down to an inevitable withdrawal, there are an increasing number of memories being published by participants. I have been looking forward to this as it is the first significant conflict without a draft. The military participants were all volunteers and professionally recruited (there is a vast difference). I’ve been interested in seeing their perception of war compared to the men who fought in earlier times against a different enemy. What I experienced when I read Gus Biggio’s book The Wolves of Helmand was déjà vu.

Frank “Gus” Biggio competed for and won a commission in the United States Marine Corps, gaining a coveted slot in the infantry back in the 1990s when the Corps was flush with cash, and overseas deployments both enjoyable and interesting. Unless you pulled a unit rotation to Okinawa in which case you were screwed. Sitting on an island where you could not train while the yen/dollar exchange rate was around 70 (meaning the dollar was damn near worthless) was misery unless you got nominated to be on the Oki Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU) in which case you got aboard naval shipping and enjoyed yourself like the rest of the Corps.

I don’t know if Gus pulled an MEU float or a unit deployment rotation to Okinawa, but he enjoyed his tour as an infantry officer. After completing his five-year obligation, he moved on, as most Marine officers do. Gus completed a law degree, got married to a physician, started a family, and was safely ensconced in Washington, D.C., when the military went to war. Gus held out for years before succumbing to a virus, planted in all Marine infantry, that makes life intolerable unless we see the elephant.

The parable of the six blind men and the elephant is an ancient Indian fable that illustrates moral relativism and religious tolerance. However, that is not the fable Gus and the rest of us are discussing; we do not embrace moral relativism and believe that religious tolerance is a God-given right. When we refer to “touching the elephant,” we are actually using a Civil War-era euphemism for experiencing combat.

Gus was in DC, working a good job, and although he’s not a name dropper, he mentions that after his morning runs, he would occasionally chat with his neighbor Michelle until she moved into the White House with her husband Barack. So, Gus was doing well on the outside, but he had a problem on the inside. His best friends were in the fight, some of them coming home on, not with, their shields. He is a highly competent adult who has sublimated a serious competitive streak towards the development of an impressive law career and a stable, thriving family. But he doesn’t yet know what his nature demands that he know, information that he’ll only know if he gets to touch the elephant. His closest friends had touched the elephant repeatedly, so his volunteering to go back in? He had no choice; I did the same thing for exactly the same reason.

Gus is precisely the kind of guy you want as your lawyer if, for no other reason, than he talked his wife into letting him deploy. He married a perceptive woman who probably understood he had to go. Still, she’s a physician, and they’re typically rule followers, so this was by any measure an impressive feat. He then signs on with the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines (1/5) and heads to Camp Pendleton, California, to start training.

From there, he deploys, with his small team, directly into the Nawa district administrative center weeks ahead of the Marine offensive that will secure that portion of the Helmand province. No air conditioning, no working toilets, no hot chow, no roof or windows, and no ability to patrol 100 meters beyond the roofless district center because the Taliban had laid siege to a small British garrison that arrived the year prior. Surrounded by Taliban, with the nearest help fifty miles distant, living in the dirt, patrolling constantly, fighting often – the entire time exposed to the elements 24/7; does that sound like fun to you? Of course not, and Gus tries to convince the reader that it wasn’t that much fun for him either. But you can tell by how hard he tries to make his experience seem like no big deal, that it was a big deal through which he earned an intangible that only those who touch the elephant can understand.

Gus is a throwback in the sense that he is a citizen soldier, not a professional Marine. As such, he joins the pantheon of Americans who wore the uniform to defend the country, not as a profession. Like all Marine reservists, he was exceptionally well trained and had years of small-unit leadership to develop his military skills. Yet still he left his young family, an obviously lucrative career in the most powerful city in the world, to get dropped into a primitive hellhole. Does that sound like normal guy behavior to you? I don’t either, but Gus is a lawyer and musters his arguments well about the reasons behind volunteering to be dropped into the middle of Indian country.

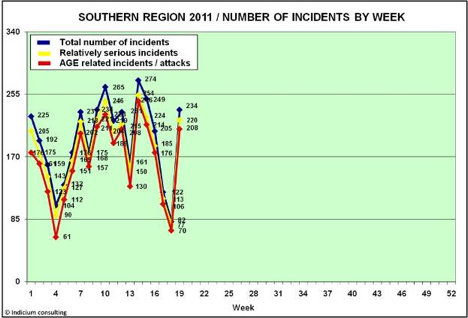

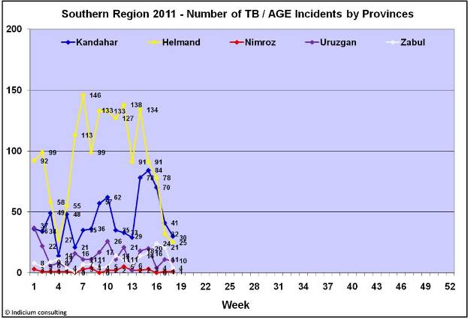

When the rest of 1/5 arrived in Nawa, they did so in a pre-dawn combat assault that overwhelmed the Taliban and drove them from the district in a matter of days. That never stopped the little T Taliban (local teens and young adults with little to do) from trying their luck with random small arms fire attacks or improvised explosive devices (IED’s) but the days of the Taliban traveling openly or intimidating the locals passed, for the most part, in most of the Helmand province.

During the year Gus spent in the Helmand province the Marine Corps actually did by the book COIN operations using a completely unsustainable deployment cycle that, while it was being sustained, was the most impressive damn thing you have ever seen. In 2010, when I moved into Lashkar Gah as the regional manager for a USIAD-sponsored Civil Development Program, I drove the roads from Lash to Nawa, to Khanashin, and to Marjha wearing local clothes in a local beater with a modest security detail and had no issues. The people seemed happy, business was thriving, and the poppy harvests were returning serious cash into the local economy.

Jagran (Major in Dari) Gus and his six Marines (and 1 corpsman) Civil Affairs Team were combat enablers for the 1st Battalion 5th Marines counterinsurgency battle. The weapon they employed was cash money, they were the carrot that offered to help the Afghan people. The Marines in the line companies were the stick, and they were everywhere, deployed in small squad-sized patrol bases in every corner of the district. Gus and his team did as much patrolling as the grunts, which they needed to do in order to deploy the money weapon. There are few times and few places in Marine Corps history where a major gets to be a gunfighter, but that is what the civil affairs team in Helmand had to do. He was a lucky man to get such a hard corps gig; he could have been deployed to a firm base support role and never left the wire, a fate worse than death for an infantryman.

Jagran Gus tells some great stories about everyday life in rural Afghanistan. I spent much time there myself and appreciate his depiction of normal Afghans going about their business. Sometimes that business involves shooting at Marines for cash and there is an interesting story about catching some teenagers in the act and letting them go to the custody of their elders after the district governor chewed them out.

It’s the little things that are telling; the Marines loved to be the stick, few things are more gratifying than a stiff firefight where you suffer no losses, and that is how the vast majority of firefights in Afghanistan went. The Marines were also perfectly cool with putting their weapons on safe and yoking up the dudes that were just shooting at them, treating their wounds, and releasing them to the district governor. It didn’t matter to them how a fight ended as long as they ended it. This type of humane treatment of wounded enemies is expected of American servicemen; it isn’t even worthy of comment in the book. I’m not saying we are the only military that does this, but most militaries don’t, and most people are amazed when we do.

My experience with Afghans in Helmand, like that of Jargan Gus, was mostly positive. That part of the world is so primitive that it’s like a time machine, where resilient people carve out an existence using primitive farming methods and minimal infrastructure. The Afghans are from old school Caucasian stock, which is why the Germans spent so much time and money there in the 1930s after Hitler came to power. They’re white people who do not have any concept of fragility and who cultivate a fierce pride in their Pashtun tribal roots. Living and working with them was an experience that is hard to capture, but Jargan Gus has done well.

Gus goes on to discuss the futility of his efforts. Nawa fell to the Taliban shortly after the Marines left in 2014. But there is no bitterness when he covers that, as there is none concerning the always turbulent re-entry into normalcy when he returned home for good. Touching the elephant always changes a man, but Jargan Gus is a bright guy who explains the unease he felt as he tried to ease back into normal life reasonably. He is a perceptive writer, and his book will be useful to future historians writing about the Afghan War. It is an excellent story about normal Americans thrust into exceptional circumstances and thriving. We need more stories like that.