Today started great, I am back in Jalalabad after completing a short job which I cannot freely blog about, and the weather is perfect. I fired up the computer and checked in with Power Line to find this excellent story about a Marine rifle platoon that 250 Taliban ambushed. They routed the Taliban and sent them fleeing from the battlefield in panic, with the designated marksmen putting down dozens of the enemy fighters using their excellent M-14 DMR. The M-14 DMR fires a 175-grain 7.62x51mm match round through a 22-inch stainless steel match grade barrel at 2,837 fps out of the muzzle. Marine marksmen can routinely hit individuals at 850 meters with this rifle, and because of the round, it has real stopping power. You won’t see a Taliban fighter take six hits with this beast and keep running (which happens frequently with the M4). You won’t see a Taliban or any other kind of human take two rounds and keep moving.

The Marine story made my day and validated something I have said repeatedly on Covert Radio which is you can move anywhere in this country with a platoon of infantry. The Taliban, rent-a-Taliban, criminals, and warlord-affiliated fighters cannot stand up to the punishment a well-trained platoon can inflict. NATO needs to learn this lesson quickly. The French lost almost a dozen men in an ambush up in the Uzbin valley in August. In that very same valley last month a force of 300 French troopers conducted a “tactical retrograde” leaving behind sophisticated anti tank missiles in the process when they were confronted by a small force of Taliban. When a much larger enemy force hit the Marines, the entire unit immediately got onto the flanks of the ambushers and rolled them up to free the men trapped in the kill zone. Once they accomplished this, they maintained contact until the Taliban broke and ran.

Conversely, the French expended all their resources and energy trying to break contact and recover casualties, a tactic not unheard of among other NATO military units. The point to all this isn’t that the Marines are great and the French army is not, but rather it’s difficult to build and sustain good infantry. NATO countries did not have to worry about producing quality infantry over the past 50 years; instead, they allowed America to shoulder that burden while they developed their economies with the money they would have otherwise needed for national defense. Producing good infantry requires a confident attitude and mindset not typically found in polite society, but when Europeans are faced with adversity, they will develop effective infantry units. You’ll know when they do because you’ll start seeing 30-man platoons from NATO countries running all over the country, hoping against hope that 200 to 300 Taliban are stupid enough to try and take them on.

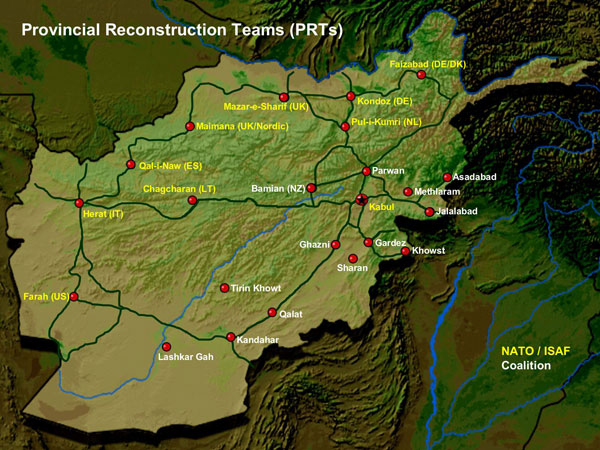

I enjoy it when events validate some of the things I say in this blog or on Covert Radio. Still, this excellent story of combat dominance will have absolutely no impact on the situation in Afghanistan at all. You cannot win here by just killing people, nor can you deal the Taliban and their affiliates a decisive blow, because they are not a unified movement, and their leaders are all in Pakistan, outside our reach. The people of Afghanistan are the prize of this contest, and a few of them are down in the Helmand or Farah Provinces. While the Marines dominate their area of operations, the rest of the country is falling outside of central government control. Every district, town, and village in Afghanistan has some ongoing land or water dispute, and land disputes here are often deadly affairs. We routinely see clashes between clans over land disputes in UN security reports, and some of these conflicts result in over a dozen casualties. When the Taliban move into an area they decide these disputes using Sharia law instead of who can pay the biggest bribe. They are considered fair in most of these rulings and will tolerate no armed fighting over disputes once a case has been decided upon. A country doesn’t lose a war against insurgents by being out-fought; they lose by being out-governed, which is exactly what is happening all over this country.

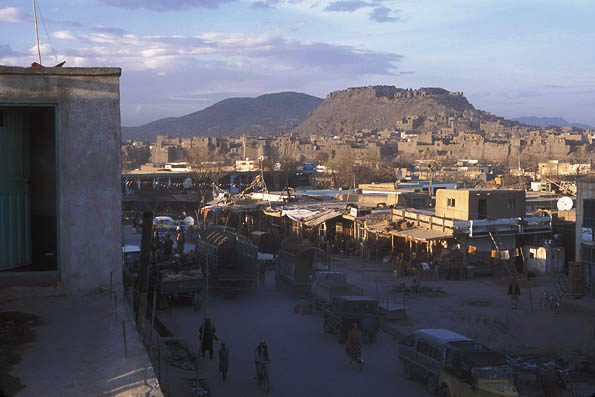

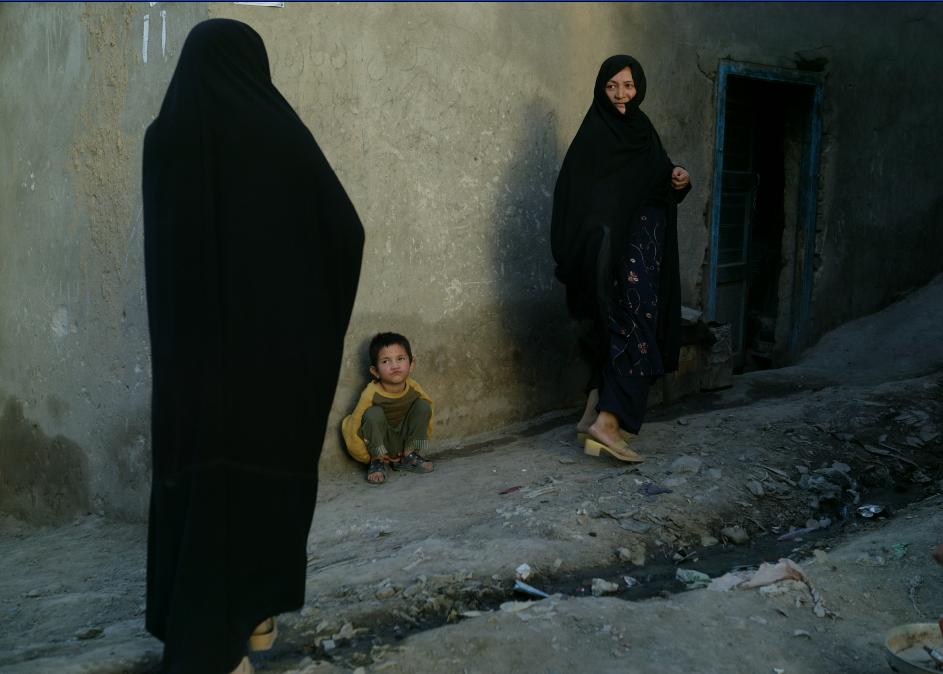

Last night, I was chatting down at the new and improved Tiki Bar with some old friends who have considerable experience in Afghanistan. One of them first came here with an NGO in 1996, and the other in 2002. Our conversation was all about change. When I first arrived in Afghanistan, it took about six hours to drive between Jalalabad, which is now a 90-minute drive. In Kabul, it was rare to see a woman who was not wearing a burka, and today the opposite is the case. In Jalalabad, which is one of the largest cities in the Pashtun belt, not all women here wear the hated burka.

However, there is a fundamental change that will never be reversed. The change you can believe in is computers and the Internet.

Computers provide access to knowledge for children who are impoverished and eager to learn about the world around them. That genie is now long out of the bottle, and my friends and I believe that the sudden surge towards modernity is spooking many of the elders who play such an important role in tribal life. We noted the backlash in Peshawar where the Pakistani Taliban is trying to reverse the headlong rush towards modernity by forcing the woman back into the burka (and with some short term success at the moment.) Peshawar used to be a very modern place that welcomed internationals and where very few women could be seen in the burka just two years ago. Not true today, and you can’t buy CDs or pirated movies either. There are many forces at play in Central Asia, and the most significant one has its momentum and will continue to generate a range of unintended consequences as it unfolds. Knowledge is power extreme poverty is motivation and the people of Afghanistan, Pakistan and all the other Stans are very motivated to acquire the power of knowledge.

We cannot control the effects of the explosive power of the internet and computers on the local people. What we can do is to continue developing the infrastructure while providing a secure environment in which the Afghans can build their economy. Security in the Afghan context requires boots on the ground doing what the Marines did in Shewan. Small units who are constantly outside the wire with the Afghan people and who crush anyone silly enough to fight them, even if they are outnumbered 20 to 1. Combat is a dangerous business, requiring men who can endure incredible hardships and discomfort while maintaining their motivation and, most importantly, a sense of humor.

Good infantry doesn’t need ice cream every day or the cushy barracks found at the Khandahar airfield; they need water, chow, lots of ammunition, and leaders who trust them. The Marine Commander down south is Colonel Duffy White, a close friend, an extraordinarily competent and experienced warrior, and a man who combines pragmatism with a great sense of humor. America has a few more like him, as do our allies. I hope to see them in-country soon, utilizing the decentralized tactics necessary to provide security to people living outside main cities and military bases.

This morning’s email contained two different security alerts about impending attacks on the vital Jalalabad-Kabul road. We have been here for almost eight years and still have not oriented our forces to provide security for the vast majority of the Afghan population. We are running out of time but it is not too late to get more of our forces oriented on the population and operating like the lone rifle platoon from the 2nd Battalion 7th Marines did in Shewan a few days ago. That requires courage from commanders on high, there are troops on the ground who already have that courage and are ready to fight like lions to give people they do not know a chance to enter the modern world. That is a worthy fight by any standard of measurement.